-

Phantom Nostalgia: The Grass Used to Be Greener, We Promise.

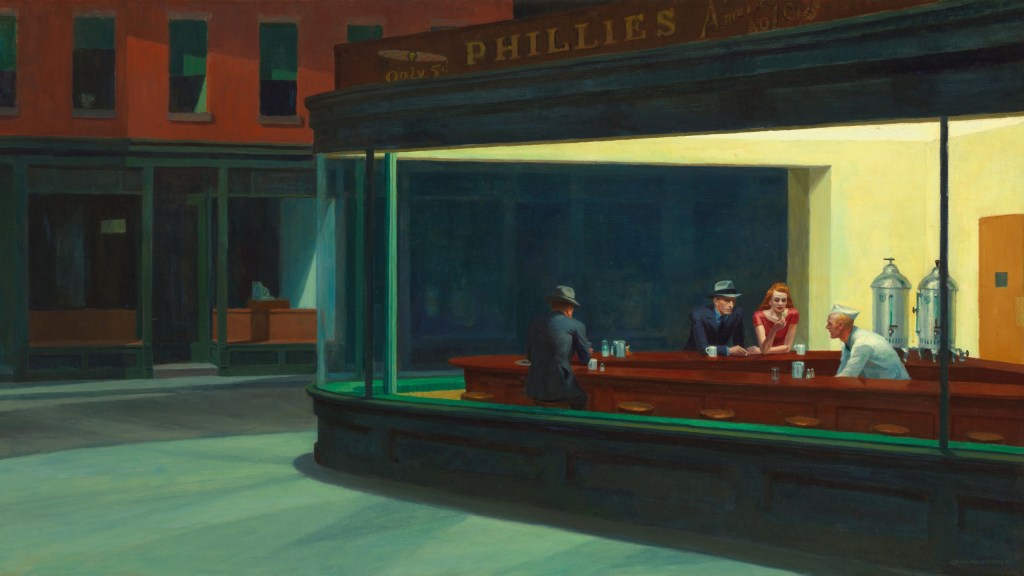

The Wheeler’s basement in Stranger Things screams 80’s nostalgia. With the release of Stranger Things Season 5’s trailer this week, my social media algorithms have been inundated with speculation and conversation by the show’s fandom. The idea of a Stranger Things stan account as always been interesting to me, especially when considering the tone (and reception) of the first season; an atmospheric sci fi mystery that wears it’s Stephen King and Spielberg influences on it’s sleeve. When show was first released, I remember the show being praised for it’s accuracy to the 80’s small town setting, or at least it’s impressive imitation of the King/Spielberg tone of their 80s’ work. I got the impression, as a preteen whose dad recommended the show, that many people’s enjoyment for the show came from it’s ability to capture something from their childhoods.

And yet, I doubt that the average Stranger Things stan account, who spends their free time speculating over which character will end the show dating who, was alive to experience the time that the show is attempting to capture. Now, as a member of Gen Z who has seen the entire show thus far, I am aware that the show has appeal beyond it’s 80’s nostalgia, but it is also undeniable that 80’s nostalgia was brought to the forefront of entertainment by shows like Stranger Things, and it is still prominent today, with many of the biggest popstars of the 2020s’ imitating 80’s synths, consistent Hollywood reboots of old IP, and fandom developing around art released within the time.

While the mainstream media is imitating decades past in a broadly comforting, unironic fashion, indie and alternative scenes are ( as you’d expect) being a little more subversive: especially in horror. Stranger Things is not without it’s scares, but the horror of Stranger Things is firmly routed in it’s 80s’ influences. Gaming and online fiction has taken the nostalgic settings of the past 30-40 years and, unlike Stranger Things, corrupted it.

Low-Poly Horror is all the rage in the indie gaming scene, imitating games from past gaming eras, yet introducing a cursed edge. Once again, the clearest explanation for what makes this trend appealing to audiences is clear: there is a simultaneous charm and horror to revisiting something from our childhood with adult eyes. That said, stopping the analysis there overlooks the massive audience online for indie horror, a large part of which simply were not alive for the time these games are referencing. Despite this, the fondness remains.

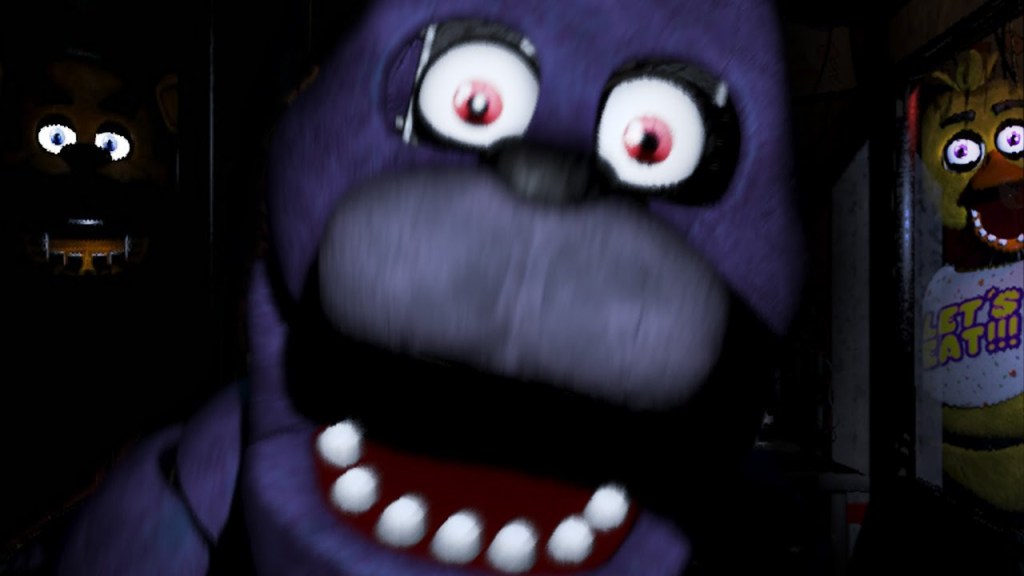

Crow Country (2024) is built on low-poly influence. I believe this disparity is often overlooked, especially with Five Nights at Freddy’s, a massive franchise for children built around distorting 80’s animatronic mascots. Especially when you consider the audience outside of America, most of the audience do not have any real memory of that FnaF references, so it’s hard to argue that the fear comes from a corruption of their nostalgic memories. Instead, it is important to remember that stripping away the horror elements of FnaF still leaves child friendly mascot designs. To somebody who has no nostalgia for this imagery, the subversion is inverted once again: instead of the horror perverting something comforting, it is softened by a gentler aesthetic. I would argue this is a large part of nostalgic horror’s success, as it makes the fear factor more accessible to younger audiences.

Nostalgic imagery is also designed to be appealing in ways beyond the acknowledgment of older things. I don’t have to have any memories of the 90’s to see a hazy photo of a 90’s bedroom, coated in band posters, lit only by the warm lighting of a PS1 game painted across the screen of a CRT to think the room looks cosy. This further explains the appeal when nostalgia is applied to horror, as this comforting edge still stands out without a personal reference point.

As a brief aside, in looking for images to puncture this post, it surprised me to discover that it wasn’t easy to find a real photo fitting the criteria described in the paragraph above, but it was incredibly easy to find a poorly rendered AI imitation. While I am certain I have seen real photos along these lines, there is something to be said about the only images I can find being wholly digital attempts at recreation. Truly, I wonder if my childhood memories are going to be smoothed over by uncanny, inhuman resemblance. I hope not.

Putting this nostalgic imagery in context is also important. We live in an era where logos are repeatedly simplified, imperfections and flair is smoothed over in entertainment; everything is cleaned. At the same time, entertainment is always encouraging a nostalgia for older visuals, there is money to be made in replicating consumer’s childhood memories. That rubs off on younger generations, who are being encouraged to fondly remember things from before their time. In this sense, franchises like Stranger Things become fully fantastical settings for younger audiences, giving them an image of a simpler time that (in reality) never existed. This false image has become a greater focus over time. It is worth noting that early seasons of Stranger things had a habit of introducing flawed characters that fit in the Stephen King esc Hawkins (Johnathan was a peeping tom, Billy was a racist) only to gloss over these complexities in the next season, redeeming the characters (and by proxy the time they’re rooted in) by ignoring the problems. Everybody knows that it’s too easy to believe that “things were simpler” when you were a child, who likely just wasn’t as privy to political, economic, and social disparity, but it is even easier to convey this concept to people who weren’t even there.

-

‘The Most Dear and the Future’ is AOTY.

ear gets as up close and personal as their name suggests.

As of writing this, ear has 272,198 monthly listeners, despite their first single, Nerves, being less than a year old, and it is far from hard to see why. The electronic/glitch pop/digital hardcore/twee pop duo feel as fresh as they are difficult to categorise, and their debut album The Most Dear and the Future feels off kilter in the most refreshing way. It’s the sort of album that will be cited years from now in conversation around other artist’s influences.

ear, aka Yaelle and Jonah. In many ways, ear feels like a series of voice notes spliced with loose ideas for songs’ but this stripped back sound creates a touching intimacy; each song feels like a snapshot or moment, quietly painting a picture by focusing on the details, big and small. It feels important to bring up the bigger moments (many of their songs contain something at least resembling a beat drop), but these larger sounds often highlight smaller choices surrounding them, especially when paired with the gentle vocals. The album’s title track, a hushed, digital reflection on moving on from a relationship, builds up to jarring industrial percussion with moments of ambient noise jumping in and out of the track. It feels like a magnifying glass on something private in the middle of something massive, or perhaps something much larger hidden in a small moment. The realisation that you don’t think about someone anymore can feel profound but usually happens in a personal moment of self reflection.

Much of ear’s work evokes this feeling to me in a way I haven’t heard before. Jonah Paz, one half of the duo, speaks about his folk-twee influences across multiple interviews, with the group noting that cute intimacy shining through their work despite clashing with their electronic hardcore soundscape, courtesy of ear’s other half Yaelle Avtan. In Jonah’s words: “ear is actually twee as shit if you think about it”.

The lo-fi digital aesthetic has quickly become a defining trait of ear’s work. Aesthetically speaking, ear revels in the online experience, both in a nostalgic sense (the video for Nerve is a mashup of seemingly random low res clips), and in a present one (Real Life’s video is screen recorded over multiple video calls). Tastefully reflecting online culture is very difficult thing to do, as it’s easy to come off as pandering, dated, or for lack of a better word, cringe. Taylor Swift recently sang about “girlbossing too close to the sun”, a line that could now easily be seen as foreshadowing for her album’s critical reception, but such “how do you do, fellow kids” energy is nowhere to be seen in ear’s online references. Instead, they look at the internet as a visual description of their intimate sound, as Nerve’s video finds random YouTube videos, niche to the point that stumbling into them feels almost invasive, and Real Life shows isolated people dancing, shared only through their cameras to the other side of a call. ear throw in some shitpost adjacent imagery too, sampling the Okay Vine in Real Life, and choosing slightly uncomfortable pixelated imagery for their covers, but there is nothing obnoxious or loud about it, but rather it furthers the feeling that you are finding something private. Despite over 200,000 monthly listeners, finding ear’s music felt to me like the algorithm suggesting a random YouTube video from a decade ago, with anywhere from 100 to a million views.

I have no idea where ear will go next, or what their legacy will be. They are currently touring with Yung Lean for the Forever Yung Tour, which gives me hope that their recognition and audience only continues to grow. How their sound will evolve is a hard to say, but after three singles and a stunning first album I’m confident they’ll continue to be worth your time.

-

What are the Backrooms for?

Turn the lights off before you go.

Subliminal releases later this year Liminal Spaces have been a defining aesthetic online for half a decade, bleeding from horror communities into low quality children’s content, brainrot, gaming, and mainstream entertainment, both through Severance (2022) and the A24’s unreleased Backrooms movie. As with most popular internet trends, this widespread attention came came with cynicism and disapproval for pretty understandable reasons. Quite frankly, most appearances of the Backrooms or similar settings are superficial, ironic, or trend-chasing, so it’s no surprise that every few months I see a comment or a quote retweet decrying the subgenre. I, however, do not share this sentiment, and between the aforementioned Backrooms film and Accidental Studios Subliminal getting a new trailer recently, I wanted to reevaluate the value of the aesthetic and narrative themes for use beyond Skibidi Toilet backdrops and memes with poor shelf lives.

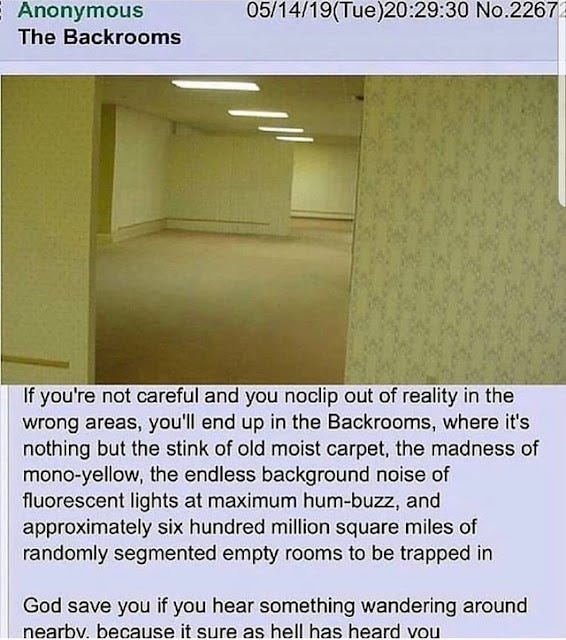

The Backrooms itself, as an idea, stems from the 4chan post pictured below, and it’s important to remember the core concept of the text: being lost in an uncanny place, equal parts afraid of being alone and of running into something. Without going into any depth on the definition of the liminal, let alone any specific features of the genre, I would argue this feeling extends to almost every story, image, or reference to the liminal space aesthetic. It might not be as literal as the posts’ reference to “something wandering around”, but the anxiety attached to feeling alone (and perhaps therefore vulnerable), is likely the easiest component of the genre to see.

This 4chan post is the originator of the Backrooms phenomenon, and helped to usher in the liminal space boom. However, seeing this anxiety’s relevance to liminal spaces might be difficult without seeing any imagery, as a “liminal space” is, in theory” simply a transitional one. In fact, the original Backrooms post does not directly refer to itself as liminal at all. That said, it does revel in the contrast that would go on to define much of the genre: nobody inhabits this space, yet the lights are on. I would argue this is the defining trait of the liminal space aesthetic: locations that appear on the edge of being lived in. The image in the backrooms is stuck in the precise moment between the space is cleared out and the lights are turned off (or arguably the moment between the lights being turned on and the space being used). In our daily lives this moment is rarely seen, or at least rarely thought about, if for no reason other than how brief it is. Google “liminal space” and you will see this moment echoed throughout the image results, admittedly with one or two creepypasta cameos photobombing the hallways.

In itself, the analysis thus far justifies liminal imagery, but I would argue it would be difficult to carry a narrative with just the established points; a frozen moment can imply a story that has or will happen, but a filmmaker might have more trouble using the idea.

Kane Parsons, director of the upcoming A24 Backrooms film, defined the genre’s most used narrative structure with his video “The Backrooms – Found Footage”. The video is largely a retelling of the original post, a guy falls into the endless yellow hallways and walks aimlessly until something abstract stalks and kills him. What makes this video significant for our purposes is the act of actually visualising somebody entering the space, and interacting with it. As simple as it sounds, this is the narrative utility to the genre: throwing a dynamic presence (i.e. a person) into a frozen, uncanny moment. Once you do this, the story becomes a two way street. What does every new discovery about the space reveal, and what does the character’s reactions reveal about them?

Kane Parson’s The Oldest View. I recommend it, so no spoilers here. Sticking with Parson’s work for a moment, an excellent use of this interaction is his series The Oldest View, where a cameraman discovers a massive staircase in the middle of nowhere, leading to a pristine 2000s shopping mall. Unlike the Backrooms, which is usually implied to be an inhuman space that only appears man made, The Oldest View’s mall is a perfect reconstruction of a real shopping centre, abandoned around the 2008 financial crisis. This makes the series’ setting a manifestation of a memory, which seems to have life (or at least electricity) breathed back into it by its’ rediscovery. The story is equal parts about the protagonist as it is about the tangible history of the place, the history that seemed to die with it, and the very real context of what destroyed it.

It feels important now to highlight another theme that lends itself to the liminal space: nostalgia. This can be seen in two clear ways. For one, I can personally attest that the lonely fear discussed earlier brings me back to my childhood, in the moments I realised I was somewhere that was about to shut, or helping out after school when the lights stayed on yet the halls were empty. The liminal space aesthetic, in all its’ uncanniness, also lends itself exceedingly well to the image of a fuzzy memory. The emptiness emphasises the metaphor of a memory, as it appears just as it is about to be abandoned; just as you left it.

The Oldest view takes this nostalgic route and zooms it out. This is not the personalised memory of a specific person, this mall is indicative of the 2000s, the final years of the shopping mall. It is hard to ignore that the 2000s also served as the stage for much of Parson’s audiences’ early years (as a brief aside, it is almost comedic how much of online horror is obsessed with the loss of our childhoods). I’d argue this is also in part why pools, play areas, and stuffy old(ish) houses are perhaps the most referenced places in Backrooms and Liminal Space content. Strangely, and perhaps due to the Backroom’s stranglehold on the genre, I cannot think of a clear example of a more personalised narrative, or character study told through the lens of the liminal space. The closest I can get is MyHouse.Wad, a Doom 2 mod that appears to be a recreation of a man’s childhood home but opens up into sprawling, mind bending maze of repeating structures and references to moments in his life, but the Doom 2 aesthetic being so baked into the mod makes it feel like a heavily related yet slightly different genre piece.

Severance offers a different angle to the genre. While the internet jumped at the opportunity to explore their nostalgia, TV’s Severance used the aesthetic for a different purpose. A clean empty space does not have to be on the verge of abandonment, it can also be laying in wait to be populated. The “Severed Floor”, where much of the show is set, is filled with unused office space, likely as the program it was made for is still getting off the ground. Severance, especially in the second season, is constantly on the precipice of an in universe revelation, and the Severed Floor reflects that.

Severance does more with the space than reflect on its’ relationship with the past and future, it is also very aware, in a very adult sense, or monotony in the present; or the 9 to 5. The show looks at the empty cleanliness of the liminal space and instead of reflecting on the past it evokes the isolation of the office space, and of a work driven culture.

To sum up, I would argue that the key use for the liminal space is to explore the passage of time, by honing in on the exact moment before or after a change, and discussing our relationship with what came before, or comes next. While the idea of a liminal space is seen by many as overdone, I would actually argue that this use hasn’t been explored in depth (beyond the inherent visual references) as much as it could be. Personally, I’m hoping that Subliminal and Parson’s A24 film both succeed in exploring this potential, and even reignite interest in other’s doing so.

-

Theory Fodder: Narrative and Marketing.

Five Nights at Freddy’s, 2014 A few years ago, I used this website for a piece of coursework on narrative through the videogame format, and now I’m resurrecting the blog for more general use. That said, in rereading my earlier posts, I had one more thought on the subject of narrative in gaming that I wanted to explore: using enigmatic and vague storytelling as a main attraction to your game.

Indie developer Scott Cawthon struck gold in 2014 when he released the first Five Nights at Freddy’s (or FNaF for short). The game lent itself incredibly well to the internet age, with ironically child friendly character designs, easy to grasp mechanics, and a tense gameplay loop that wasn’t only fun to play, but also to watch people online experience for the first time.

More relevant to this blog post, however, is the incredibly vague storyline: you are a security guard at a family restaurant, and you have to make it through five shifts while the Chuck E. Cheese esc animatronics try to murder you. Not long after the game’s release, Matthew Patrick (Also known as MatPat) uploaded a video to his YouTube Channel Game Theory, which attempted to solve the FNaF story. As it stands, this video has 35 million views, redefining the Game Theory channel, online horror, and indie gaming horror ever since.

With every subsequent FNaF game Cawthon released, and every Game Theory response that inevitably followed, it became increasingly clear that the ever expanding storyline wasn’t vague because it was simple (at least not anymore), the vagueness was a way to keep the audience hooked on the franchise. With every release came a massive community response to decipher every pixel in the game, searching for the puzzle piece that finally put the mystery to rest.

This is hardly an entirely new idea. JJ Abrams has talked about approaching stories with a “Mystery Box”, holding his audience’s attention by presenting them with an interesting mystery to solve, and mystery has essentially existed as it’s own genre since the 1800s. Unlike FNaF, When you read a Sherlock Holmes’ novel, or watch Lost, there is still an intended, cohesive viewing experience. FNaF throws cohesive storytelling out of the window, instead burying tidbits of information, sometimes in seemingly random order, all over the place, in hopes that the community will piece it together themselves. Occasionally, the games will confirm a theory, or reveal a large piece of the puzzle, but this is usually attached to a new part of the mystery also being revealed, keeping the audience engaged.

Regardless of your feelings on the now hugely successful, multimedia franchise of FNaF, let’s acknowledge this approach to storytelling for what it is: an incredible marketing tactic. MatPat, and the influencer ecosystemn he inspired, became the marketing team for a franchise whose first game was made by one guy with next to no budget.

As you can imagine, the indie scene took notice, especially in horror gaming. The term “Mascot Horror” has been coined to refer to the more overt riffs on FNaF’s aesthetic, but there has also been a noticeable pivot towards enigmatic storytelling for the sake of marketing. If you got a Game Theory video, you immediately garnered an audience. “Analog Horror”, an online film movement that grew parallel to these events, also embraced theory baiting. It feels important to note that all of this was preceded by the existence of Alternate Reality Gaming, a multimedia format that often cuts out the middle-man and exists as raw narrative puzzle-solving.

Now, with all of that context, and a healthy dose of cynical explanation, we can talk about how valuable this is purely from the perspective of somebody trying to tell a compelling story. On the one hand, it can be a compelling experience to deep dive into a community’s effort to solve a story, it makes you feel involved in something. It also lets the audience find their own meaning in the story. Dissenting opinions over a storyline’s details can act as a Rorschach test, people will gravitate to specific ideas and feel differently about a story’s meaning.

At the same time, a story built on the promise of a satisfying secret buried somewhere within it is putting itself under a lot of pressure to deliver. FNaF’s response to this is to simply never end; why give an answer to your mystery if you can just keep making the mystery larger? While this is great for FNaF as a franchise, it isn’t necessarily as good for the quality of the plot. Shows like Abrams’ Lost also saw dwindling viewership as audiences grew dissatisfied with the few answers they received. Even a cursory look at Game Theory’s FNaF videos shows that the views, while still strong, aren’t exactly what they used to be.

Crafting an intentionally vague narrative is, frankly, a great approach to marketing, especially when paired with an engaging aesthetic or setting, but with over a decade between us and the first FNaF’s release, it is growing harder to see the difference between a bold, enigmatic narrative device and a clever advertising formula.

Not wanting to completely dismiss stories made in this vein, I wanted to throw in two recommendations for great examples that fit the label:

Petscop is what I would cite as the gold standard for mysterious internet horror. Horror may not even be the most fitting word, but I can’t name another example that uses mystery and the implicit to build as satisfying and haunting of a storyline.

Any FromSoftware game will likely have an easy enough plot to follow on the surface, but pays incredible attention to the dense world with little exposition. Every game they make hides multiple amazing plots behind context clues, and even if you don’t enjoy the gameplay it is worth googling some narrative analysis.

-

Additional Content: Self Made Story

Minecraft, 2011 The three previous posts on this blog were originally designed to represent a cohesive discussion of the different ways developers can use videogames to convey a story to the audience, however due to some extra time I have decided to add at least one side point to discuss the relationship between narrative and play. This post will focus on narrative made largely through player choice in a situation where said story is not intentionally provided by developers.

Let’s start with a personal example of self made story within a story based game. I remember when Elden Ring first released, I showed up to a class and chatted with a friend, and the game came up. However, what I found interesting is we both told stories about the vastly different journeys we had both been on within the game, as if we were describing completely different stories. Due to our ability to both build very different characters, and our ability to explore the world in our own way led to entirely different narratives.

Now, we were both bound by the main story of Elden Ring to some extent. On one level, we were both encouraged to focus on the main story, so our narratives had clear crossovers, and on another level we both started in the same area of the same world, so at the very least our settings were the same. It is very rare for a game to overcome this.

One example of a game that takes a step further away from providing any narrative is Minecraft. The game puts the player in a randomly generated world and gives them no story or incentive through quests, meaning that players are free to do what they please within the sandbox. There is always bound to be crossover when players discuss unique experience with Minecraft, as doing specific notable tasks like exploring “the Nether”, a sort of hell dimension, create clear points of comparison. The game also plays the end credits after defeating “the Ender Dragon”, which implies an end to the story (it is worth noting that Minecraft does not stop you from playing after doing so). That said, the game once again leads to entirely unique stories between players, as the game is randomly generated (and lacking in incentive) enough for every playthrough to be different. While this storytelling does not allow for as much creator control over theme, it instead gives it to players who, likely without realising, craft a more personal story.

-

Theme Through Non-Linearity

Silent Hill 2, 2001 Player involvement is the key difference between videogames and all other artistic mediums. Previously, this blog has gone over how this affects the audience experience in a fairly surface level way, but this post will go over how the theme of a game can be uniquely expressed through the medium, especially when games lack linearity in both gameplay and narrative.

Much as individual players will have unique experiences of the character they play through their own gameplay, they may also reach their own conclusions on the themes of a game through what they experience. Once again, the works of FromSoftware are excellent at creating an individualistic thematic experience for this. Dark Souls III is a great example, as many key details in the story are hidden in secret areas and behind completion of side quests.

The goal of Dark Souls III, on the surface, is to “link the first flame” to continue “the Age of Fire”, which is the same goal as the first game in the franchise. However, whilst the time since the first game is never stated, it is heavily implied that the age of fire has been prolonged for an unnatural amount of time: characters and landscapes are rotting and decaying, and the first flame (which was a large fire in the first instalment) is now a tiny ember if linked. Through finding a secret item and giving it to a specific character, the player can find an alternate ending where you refuse to link the first flame and bring about a new age (“the Age of Dark”). There is also an even more convoluted path to another secret ending, wherein you become the ruler of “the Age of Hollows”. What is interesting about these hidden endings, is each one changes the context of the others. The Age of Dark ending paints the first ending as a negative conclusion, when that may not be clear without the context of the second ending, and the Age of Hollows ending reveals a broader context of the world, as it suggests a vying for control over the next age that again is less clear without discovering the ending.

All of this creates very different impressions of the game to each player, as somebody who only sees the first ending and does little exploration of side content will remain unaware of the potential better/worse endings. Now, an interesting question to raise here is whether the undiscovered content still informs the themes of the game or if whatever the player experiences is all that matters for their discussion of the game’s themes. If undiscovered content matters, then the game must always be viewed as a complete artistic statement, where it is irrelevant what the player experiences, and all that matters is that the player can experience everything. If not, then a videogame must be seen as more as a tool for letting the player reach personal conclusions on the subjects discussed.

To me, it depends on the game. A game like Dark Souls III works best as a complete experience, with details undiscovered by the player still being worth considering when discussing what the game is saying. However, a game like Silent Hill 2, which tells a far more personal story, is perhaps more interesting if the individual player experience is given more thought, as the player’s behaviour reflects the protagonist’s conclusions in the story, so only considering what the player is aware of can create an interesting discussion regarding how they consider the game’s artistic statement. This can also apply well to RPGs like Fallout: New Vegas, due to the encouragement of player choice.

For some games, the mere fact that there are multiple endings or content likely to go undiscovered by the player is what matters. Most clearly, games like The Stanley Parable uses branching paths as a primary point of the gameplay, with the incentive to keep playing being replay value, to find new endings. Other games such as Outer Wilds, which focuses on exploring a miniature galaxy over and over again in a groundhog day styled situation, the potential inability a player has to discover everything the game offers in itself offers an interesting point of analysis.

-

Character Through Player Choice

Halo 3, 2007 In the previous post, I outlined how videogames can use the setting to convey a narrative, but it is also important to note the importance that player choice can have in a story. Some games are built around this idea, such as the work of Telltale Games (most famously their Walking Dead series), while some do very little to give the player direct involvement in the narrative, which is not to say players have no effect.

As previously mentioned, The Walking Dead is a great example of overt player involvement in narrative, as it is designed entirely around letting the player make decisions (both big and seemingly small) on behalf of the protagonist. This creates a clear investment from the audience in the protagonist’s story, as not only do you relate to them, but through making choices for the playable character the line between audience member and protagonist is blurred.

Role Playing Games (RPGs) also have some of the clearest examples of player involvement in the narrative. Many RPGs feature a character creation system, and/or let the player decide how the protagonist will behave throughout the story. The effect of this is in the name; by allowing control over the main character even down to their appearance, Role Playing Games let the player immerse themselves within the fantasy of existing within the setting. In some cases, this afforded choice can appear illusory, as giving the player a set of choices can feel limited if the player wants to do something the choices don’t cover, highlighting the game’s limitations (ironically more than entirely linear games, as the lack of choice in those often remove the thought of player freedom from the audience entirely).

Something worth acknowledging is subtle effect that the player has over the their relationship to the narrative in theoretically linear experiences. In first person shooters like Halo’s single player campaigns the player is essentially walked through the story with no choice: to finish the game, the protagonist “Master Chief” is required to shoot hordes of aliens in specific locations, laid out chronologically. However, even though the plot itself cannot be changed, the player has a surprising amount of control over smaller details that can change their view of the experience. One player may try to stick to long range weapons, changing Master Chief into an elite sniper figure, whilst others may play the role of a duellist through the use of pistols and shotguns. Some players might charge through the story and take it very seriously, rarely taking damage, whereas others might slowly walk through each level, joking around and almost dying at every turn. In the first example, Halo is a serious action epic, yet in the other it is an action/slapstick comedy, despite the written narrative remaining unchanged. Each player will view Halo differently because of the behaviour they demonstrated when controlling Master Chief.

-

Storytelling Through Level Design

Bloodborne, 2015 When discussing narrative opportunities provided by the videogame format, perhaps the clearest example is the use of environmental storytelling. This is where the level design is used for exposition, instead of dialogue and character action telling the story. Many games do this mostly for the sake of worldbuilding, and still tell their stories through character action. Bioshock, for example, uses environmental storytelling to explain the backstory of each level’s boss, and give information about the setting, but it still features plenty of dialogue and action that drives the story.

Of course, this is not unique to the medium of videogames: Any artistic medium that can depict a setting is capable of environmental storytelling. Due to the player’s ability to control a protagonist, however, and therefore to explore and fixate upon elements of the world at their own pace, it is uniquely positioned to greater emphasise worldbuilding and narrative through setting. Games made by FromSoftware, such as Dark Souls and Bloodborne, are well known for their cryptic narratives, as little information is directly given to the player. Instead, information is given to the player as a reward for exploration, incentivising focus and engagement with the world. Hiding key plot details in Bloodborne, such as the secret boss “Ebrietas, Daughter of the Cosmos” within established areas, such as the Upper Cathedral Ward, reveals the religious organisations connections to the creature, and explaining where they are obtaining the alien blood that is corrupting the city, or at least one source of it.

An interesting consistency between games that emphasise environmental storytelling is the apocalypse, societal collapse, or some form of abandoned space. This makes sense, as it is intriguing to present a player with such a setting without directly clarifying why the location is as it is, creating a mystery for the player to unravel. Such settings also typically lack many (friendly) NPCs, so it is harder to have a character give direct exposition without it feeling forced.

The ability to emphasise environmental storytelling in videogames is certainly a strength of the medium, as the player’s involvement in exploration will likely keep them engaged in a way that they may not be if simply watching a film or reading a book. A two hour film where a silent protagonist explores a post apocalyptic city with no dialogue would not reach a large audience, but plenty of games give the player exactly that experience for longer periods of time, and it is more engaging.