A few years ago, I used this website for a piece of coursework on narrative through the videogame format, and now I’m resurrecting the blog for more general use. That said, in rereading my earlier posts, I had one more thought on the subject of narrative in gaming that I wanted to explore: using enigmatic and vague storytelling as a main attraction to your game.

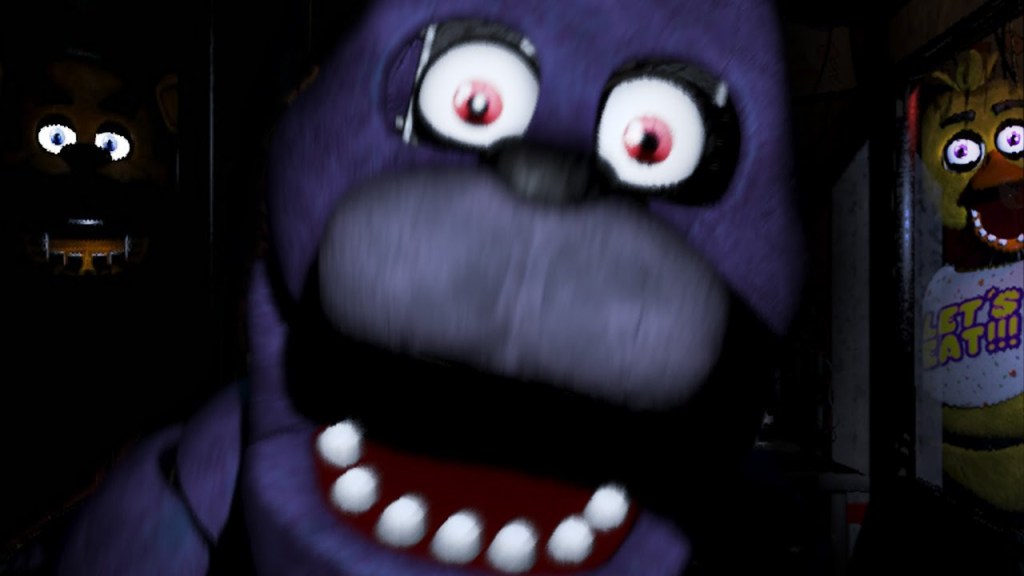

Indie developer Scott Cawthon struck gold in 2014 when he released the first Five Nights at Freddy’s (or FNaF for short). The game lent itself incredibly well to the internet age, with ironically child friendly character designs, easy to grasp mechanics, and a tense gameplay loop that wasn’t only fun to play, but also to watch people online experience for the first time.

More relevant to this blog post, however, is the incredibly vague storyline: you are a security guard at a family restaurant, and you have to make it through five shifts while the Chuck E. Cheese esc animatronics try to murder you. Not long after the game’s release, Matthew Patrick (Also known as MatPat) uploaded a video to his YouTube Channel Game Theory, which attempted to solve the FNaF story. As it stands, this video has 35 million views, redefining the Game Theory channel, online horror, and indie gaming horror ever since.

With every subsequent FNaF game Cawthon released, and every Game Theory response that inevitably followed, it became increasingly clear that the ever expanding storyline wasn’t vague because it was simple (at least not anymore), the vagueness was a way to keep the audience hooked on the franchise. With every release came a massive community response to decipher every pixel in the game, searching for the puzzle piece that finally put the mystery to rest.

This is hardly an entirely new idea. JJ Abrams has talked about approaching stories with a “Mystery Box”, holding his audience’s attention by presenting them with an interesting mystery to solve, and mystery has essentially existed as it’s own genre since the 1800s. Unlike FNaF, When you read a Sherlock Holmes’ novel, or watch Lost, there is still an intended, cohesive viewing experience. FNaF throws cohesive storytelling out of the window, instead burying tidbits of information, sometimes in seemingly random order, all over the place, in hopes that the community will piece it together themselves. Occasionally, the games will confirm a theory, or reveal a large piece of the puzzle, but this is usually attached to a new part of the mystery also being revealed, keeping the audience engaged.

Regardless of your feelings on the now hugely successful, multimedia franchise of FNaF, let’s acknowledge this approach to storytelling for what it is: an incredible marketing tactic. MatPat, and the influencer ecosystemn he inspired, became the marketing team for a franchise whose first game was made by one guy with next to no budget.

As you can imagine, the indie scene took notice, especially in horror gaming. The term “Mascot Horror” has been coined to refer to the more overt riffs on FNaF’s aesthetic, but there has also been a noticeable pivot towards enigmatic storytelling for the sake of marketing. If you got a Game Theory video, you immediately garnered an audience. “Analog Horror”, an online film movement that grew parallel to these events, also embraced theory baiting. It feels important to note that all of this was preceded by the existence of Alternate Reality Gaming, a multimedia format that often cuts out the middle-man and exists as raw narrative puzzle-solving.

Now, with all of that context, and a healthy dose of cynical explanation, we can talk about how valuable this is purely from the perspective of somebody trying to tell a compelling story. On the one hand, it can be a compelling experience to deep dive into a community’s effort to solve a story, it makes you feel involved in something. It also lets the audience find their own meaning in the story. Dissenting opinions over a storyline’s details can act as a Rorschach test, people will gravitate to specific ideas and feel differently about a story’s meaning.

At the same time, a story built on the promise of a satisfying secret buried somewhere within it is putting itself under a lot of pressure to deliver. FNaF’s response to this is to simply never end; why give an answer to your mystery if you can just keep making the mystery larger? While this is great for FNaF as a franchise, it isn’t necessarily as good for the quality of the plot. Shows like Abrams’ Lost also saw dwindling viewership as audiences grew dissatisfied with the few answers they received. Even a cursory look at Game Theory’s FNaF videos shows that the views, while still strong, aren’t exactly what they used to be.

Crafting an intentionally vague narrative is, frankly, a great approach to marketing, especially when paired with an engaging aesthetic or setting, but with over a decade between us and the first FNaF’s release, it is growing harder to see the difference between a bold, enigmatic narrative device and a clever advertising formula.

Not wanting to completely dismiss stories made in this vein, I wanted to throw in two recommendations for great examples that fit the label:

Petscop is what I would cite as the gold standard for mysterious internet horror. Horror may not even be the most fitting word, but I can’t name another example that uses mystery and the implicit to build as satisfying and haunting of a storyline.

Any FromSoftware game will likely have an easy enough plot to follow on the surface, but pays incredible attention to the dense world with little exposition. Every game they make hides multiple amazing plots behind context clues, and even if you don’t enjoy the gameplay it is worth googling some narrative analysis.

Leave a comment