Turn the lights off before you go.

Liminal Spaces have been a defining aesthetic online for half a decade, bleeding from horror communities into low quality children’s content, brainrot, gaming, and mainstream entertainment, both through Severance (2022) and the A24’s unreleased Backrooms movie. As with most popular internet trends, this widespread attention came with cynicism and disapproval for pretty understandable reasons. Quite frankly, most appearances of the Backrooms or similar settings are superficial, ironic, or trend-chasing, so it’s no surprise that every few months I see a comment or a quote retweet decrying the subgenre. I, however, do not share this sentiment, and between the aforementioned Backrooms film and Accidental Studios Subliminal getting a new trailer recently, I wanted to re-evaluate the value of the aesthetic and narrative themes for use beyond Skibidi Toilet backdrops and memes with poor shelf lives.

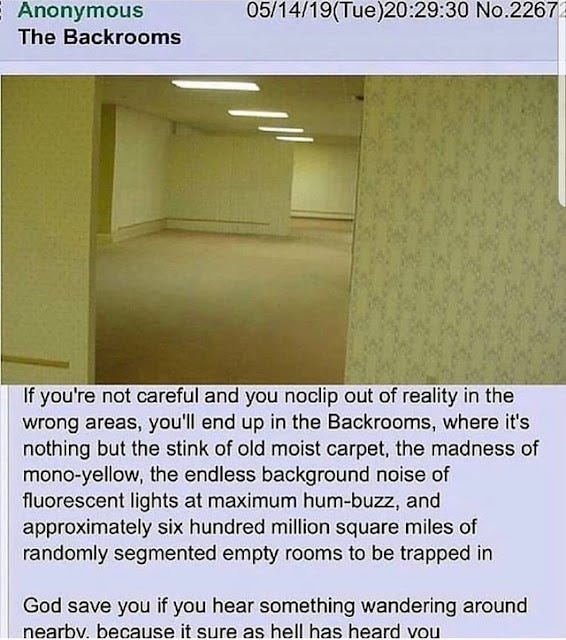

The Backrooms itself, as an idea, stems from the 4chan post pictured below, and it’s important to remember the core concept of the text: being lost in an uncanny place, equal parts afraid of being alone and of running into something. Without going into any depth on the definition of the liminal, let alone any specific features of the genre, I would argue this feeling extends to almost every story, image, or reference to the liminal space aesthetic. It might not be as literal as the posts’ reference to “something wandering around”, but the anxiety attached to feeling alone (and therefore vulnerable), is likely the easiest component of the genre to see.

However, seeing this anxiety’s relevance to liminal spaces might be difficult without seeing any imagery, as a “liminal space” is, in theory simply a transitional one. In fact, the original Backrooms post does not directly refer to itself as liminal at all. That said, it does revel in the contrast that would go on to define much of the genre: nobody inhabits this space, yet the lights are on. I would argue this is the defining trait of the liminal space aesthetic: locations that appear on the edge of being lived in. The image in the backrooms is stuck in the precise moment between the space is cleared out and the lights are turned off (or arguably the moment between the lights being turned on and the space being used). In our daily lives this moment is rarely seen, or at least rarely thought about, if for no reason other than how brief it is. Google “liminal space” and you will see this moment echoed throughout the image results, admittedly with one or two creepypasta cameos photobombing the hallways.

In itself, the analysis thus far justifies liminal imagery, but I would argue it would be difficult to carry a narrative with just the established points; a frozen moment can imply a story that has happened or will happen, but a filmmaker might have more trouble using the idea.

Kane Parsons, director of the upcoming A24 Backrooms film, defined the genre’s most used narrative structure with his video “The Backrooms – Found Footage”. The video is largely a retelling of the original post, a guy falls into the endless yellow hallways and walks aimlessly until something abstract stalks and kills him. What makes this video significant for our purposes is the act of actually visualising somebody entering the space, and interacting with it. As simple as it sounds, this is the narrative utility to the genre: throwing a dynamic presence (i.e. a person) into a frozen, uncanny moment. Once you do this, the story becomes a two way street. What does every new discovery about the space reveal, and what does the character’s reactions reveal about them?

Sticking with Parson’s work for a moment, an excellent use of this interaction is his series The Oldest View, where a cameraman discovers a massive staircase in the middle of nowhere, leading to a pristine 2000s shopping mall. Unlike the Backrooms, which is usually implied to be an inhuman space that only appears man made, The Oldest View’s mall is a perfect reconstruction of a real shopping centre, abandoned around the 2008 financial crisis. This makes the series’ setting a manifestation of a memory, which seems to have life (or at least electricity) breathed back into it by its’ rediscovery. The story is equal parts about the protagonist as it is about the tangible history of the place, the history that seemed to die with it, and the very real context of what destroyed it.

It feels important now to highlight another theme that lends itself to the liminal space: nostalgia. This can be seen in two clear ways. For one, I can personally attest that the lonely fear discussed earlier brings me back to my childhood, in the moments I realised I was somewhere that was about to shut, or helping out after school when the lights stayed on yet the halls were empty. The liminal space aesthetic, in all its’ uncanniness, also lends itself exceedingly well to the image of a fuzzy memory. The emptiness emphasises the metaphor of a memory, as it appears just as it is about to be abandoned; just as you left it.

The Oldest view takes this nostalgic route and zooms it out. This is not the personalised memory of a specific person, this mall is indicative of the 2000s, the final years of the shopping mall. It is hard to ignore that the 2000s also served as the stage for much of Parson’s audiences’ early years (as a brief aside, it is almost comedic how much of online horror is obsessed with the loss of our childhoods). I’d argue this is also in part why pools, play areas, and stuffy old(ish) houses are perhaps the most referenced places in Backrooms and Liminal Space content. Strangely, and perhaps due to the Backroom’s stranglehold on the genre, I cannot think of a clear example of a more personalised narrative, or character study told through the lens of the liminal space. The closest I can get is MyHouse.Wad, a Doom 2 mod that appears to be a recreation of a man’s childhood home but opens up into sprawling, mind bending maze of repeating structures and references to moments in his life, but the Doom 2 aesthetic being so baked into the mod makes it feel like a heavily related yet slightly different genre piece.

While the internet jumped at the opportunity to explore their nostalgia, TV’s Severance used the aesthetic for a different purpose. A clean empty space does not have to be on the verge of abandonment, it can also be laying in wait to be populated. The “Severed Floor”, where much of the show is set, is filled with unused office space, likely as the program it was made for is still getting off the ground. Severance, especially in the second season, is constantly on the precipice of an in universe revelation, and the Severed Floor reflects that.

Severance does more with the space than reflect on its’ relationship with the past and future, it is also very aware, in a very adult sense, or monotony in the present; or the 9 to 5. The show looks at the empty cleanliness of the liminal space and instead of reflecting on the past it evokes the isolation of the office space, and of a work driven culture.

To sum up, I would argue that the key use for the liminal space is to explore the passage of time, by honing in on the exact moment before or after a change, and discussing our relationship with what came before, or comes next. While the idea of a liminal space is seen by many as overdone, I would actually argue that this use hasn’t been explored in depth (beyond the inherent visual references) as much as it could be. Personally, I’m hoping that Subliminal and Parson’s A24 film both succeed in exploring this potential, and even reignite interest in other’s doing so.

Leave a comment